ALBANIA UNDER PRINCE WIED

The Dutch Military Mission to Albania 1913 - 1914

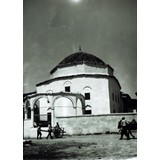

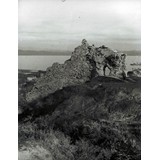

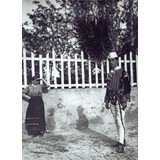

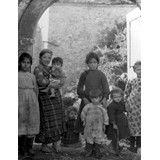

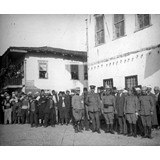

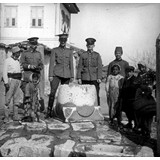

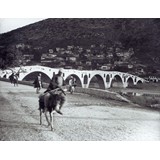

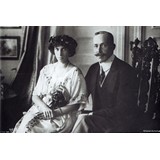

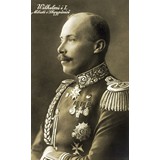

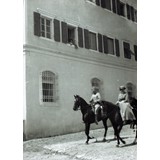

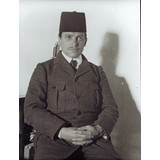

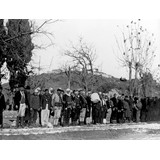

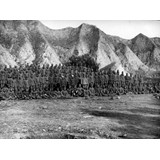

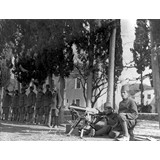

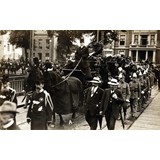

English | Shqip Acknowledgement Each of the Dutch officers sent to Albania in 1913-1914 to set up the gendarmerie of the newly created Albanian State was seconded to the Balkans not only with his normal military equipment, but also - to our good fortune - with a camera. The men recorded what they saw and experienced at a defining moment in Albanian history: the nation’s late independence after five hundred years of Ottoman rule, the arrival of a new German sovereign to reign over his tiny Balkan kingdom, and the country’s descent into chaos precipitated by domestic strife, the Balkan Wars and the outbreak of World War I. Many of the photos of the Dutch officers have survived the decades to be presented here. Most of the pictures have never been seen by the general public before. Photo Captions This photo collection, first published in the album Writing in Light: Early Photography of Albania and Southwest Balkans, Prishtina 2007, contains many unique views of a lost world, ones which are sure to captivate all those interested in Albanian and Balkan history. We are grateful to the families of the Dutch officers, many of whom preserved the collections of old glass slides and offered them generously for this publication. Thanks go, in conclusion, to others who have helped make the collection available, among whom: the Netherlands Institute for Military History (Nederlands Instituut voor Militaire Historie) in The Hague and its documentalist Okke Groot, as well as Durim Bani (The Hague), Jolien Berendsen-Prins of the Thomson Foundation (Groningen), Kastriot Dervishi (Tirana), Gerda Mulder of the Nederlands Fotomuseum (Rotterdam), Harrie Teunissen (Leiden) and Richard van den Brink (Utrecht). History of the Dutch Military Mission Albania was part of the Ottoman Empire from the age of the Turkish conquest of the southwestern Balkan Peninsula in about 1390-1400 to the final collapse of the once mighty realm, then known as the Sick Man of Europe, in 1912. In the course of these five centuries, most of the originally Christian population had converted to Islam and adopted the customs and lifestyle of the Orient. Albanians also made a substantial contribution to the Ottoman Empire. Many viziers, grand viziers (prime ministers) and high administrative and military figures ruling the Empire were of Albanian origin. It was in the last decades of the nineteenth century, a period of sharp decline in the fortunes of the Ottoman Empire, that an Albanian national movement arose. For the first time, ethnic identity became more important among the educated population than religious affiliation or imperial glory. The Albanians increasingly longed for autonomy and self-determination within the Empire - the thought of political independence was as yet a distant dream. This movement, known as Rilindja (Rebirth), crystallised in the so-called League of Prizren in the years 1878-1881. Yet despite the awakening of a national movement, Albania was to be ruled from Constantinople for another thirty years. In July 1908, the Ottoman Empire was finally shaken out of its lethargy by the Revolution of the Young Turks. This internal revolt initially received substantial support from Albanian leaders in Istanbul and Thessalonica. Nonetheless, soon after it had occurred, most educated Albanians came to realise that, with regard to demands for Albanian autonomy within the Empire, the Young Turks were no better than the old. With none of their grievances met, Northern Albania and Kosova were in almost constant revolt from 1909 to 1912. Albania did not play a prominent role in the Balkan Wars that raged in the Peninsula in 1912-1913, although, as a de facto part of the Ottoman Empire, it did not escape the conflagration. During the first Balkan War from October 1912 to May 1913, the Albanians found themselves in an extremely awkward position, between a rock and a hard place. There had been numerous major uprisings in Albania against the Turks, but Albanian leaders were now more concerned about the expansion of the coalition of Christian forces in Montenegro, Serbia and Greece than they were about the weakened Ottoman military presence in their country. What they wanted was to preserve the territorial integrity of Albania. Within two months, Ottoman forces had all but capitulated, and it was only in Shkodra and Janina that Turkish garrisons were able to maintain position for a while. The very existence of the country was threatened. It was at this time that Ismail Kemal bey Vlora (1844-1919), known in Albanian as Ismail Qemali, returned to Albania with Austro-Hungarian support and declared Albanian independence in the town of Vlora on 28 November 1912. Though this declaration of independence proved historic for the Albanian people, it was more theoretical than real. The Montenegrins had taken Lezha and Shëngjin and were besieging Shkodra; the Serbs had seized not only Kosova and western Macedonia, but also Elbasan, Tirana and Durrës; and the Greeks had invaded Saranda and stationed their forces on the island of Sazan outside the Bay of Vlora. Fighting continued in and around Shkodra from March until May 1913, by which time both Turkish and Serb troops began to withdraw from the country. Albanian independence was given international recognition at the so-called Conference of the Ambassadors, held in London in 1912-1913. This conference of the six Great Powers (Britain, France, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Russia and Italy) began its work at the Foreign Office on 17 December 1912 under the direction of the British foreign secretary, Sir Edward Grey (1862-1933). With regard to Albania, the ambassadors had initially decided that the country would be recognized as an autonomous state under the sovereignty of the sultan. After much discussion, however, they reached a formal decision on 29 July 1913 that Albania would be an autonomous, sovereign and hereditary principality by right of primogeniture, guaranteed by the six Powers. Albanian independence had thus been recognized, even though the authority of the new Albanian provisional government, formed on 5 July 1913, did not extend much beyond Vlora. The new sovereign was to be designated by the six Great Powers upon the proposal of the two most-interested nations, Austria-Hungary and Italy. Their choice fell upon the German prince, Wilhelm zu Wied (1876-1945). Prince Wied was born of a noble protestant family in Neuwied on the Rhine, situated between Bonn and Koblenz. His mother was Marie, Princess of Holland. An officer in the Prussian army, Wied was a cousin of the German Emperor, and was the nephew of Queen Elizabeth of Romania. He was married to Princess Sophie (1885-1936) of Schönburg- Waldenburg in Saxony. In October 1913, the Great Powers offered him, as a compromise candidate, the throne of the newly independent country of Albania, a land about which he knew very little at the time. On 1 November 1913, after due reflection and imposing certain conditions of his own, Wied agreed to accept the Albanian throne, and arrived in Durrës on 7 March 1914 aboard the Austro-Hungarian naval vessel Taurus. The chaotic political situation both within Albania and with Albania’s neighbours made it virtually impossible for the well-meaning prince to reign. Left to fend for himself, he received little or no financial or military backing from abroad, in particular as a result of the outbreak of World War I. On 3 September 1914, after six months on the throne, Wied abandoned Albania aboard the Italian vessel Misurata, though without formally abdicating. He never returned. In July 1913, the newly recognized principality of Albania needed not only a sovereign, but also fixed borders, a government and - what was of no small significance - a military police force to guarantee the prince’s rule and to ensure law and order in the country. The Conference of Ambassadors resolved that public order and security should be assured by an internationally organised gendarmerie. This police force was to be in the hands of foreign officers who would exercise effective command and control. The officers were originally to be selected from the Swedish army. The Kingdom of Sweden was, however, busy with a similar mission in Persia, so the choice then fell upon the Netherlands, in particular because the country was neutral, had no direct interests in Albania, and no doubt because it had a good deal of colonial experience in the Dutch East Indies where there was a large Muslim population. On 1 August 1913, the Dutch Government was officially requested to furnish officers to help restore order to Albania. On 19 September of that year, after internal discussions, the Netherlands notified the International Control Commission (ICC) that it had accepted the request and would make Dutch officers available for the mission to Albania. The War Minister Hendrikus Colijn contacted his friend, Major Lodewijk Thomson (1869-1914), a well-known political and military figure of the age, and inquired if he would be interested. Thomson, born in Voorschoten near the Hague on 11 June 1869, had been a Liberal Union member of parliament for Leeuwarden between 1905 and 1912, and had gained military experience in the Dutch East Indies (especially in northern Sumatra), as an observer in the Boer War, and at the siege of Janina in northern Greece and in Shkodra during the first Balkan War. Before his appointment as head of the Dutch mission to Albania could be finalized, however, the cabinet resigned, and the new War Minister Bosboom decided that other potential candidates for the post needed to be considered. For this reason, the definitive appointment of a head of mission was delayed, despite official agreement on an advanced secondment. When the choice was finally made, by a Royal Decree of 20 October 1913, it fell upon Colonel Willem De Veer, Commander of the 3rd Field Artillery Regiment, with Thomson of the 12th Infantry Regiment as his second-in-command. This constellation proved awkward because De Veer lacked Thomson’s organizational talent and experience. The advanced mission of the two Dutch officers and their two adjutants, sergeants Van Reijen and Stok, arrived on 10 November 1913 in Vlora, the seat of the provisional government and of the International Control Commission. Much time had been wasted and they wanted to tour the country immediately to get a feel for the problems with which they would be faced. Turkish, Serb and Montenegrin troops had withdrawn from Albania proper, but there was no unity within the country. Much of central Albania, north of Vlora, was under the authority of Essad Pasha Toptani (1864-1920), who has gone down in Albanian history as one of the more devious, conniving and self-interested figures the country has ever produced. On 16 October 1913 Essad Pasha had formed his own Government of Durrës, encompassing the coastal region from the Mat to the Shkumbin rivers. Departing on 20 November 1913, the Dutch officers were accompanied by Melek bey Frashëri, who subsequently became Thomson’s adjutant, and by Et’hem bey Vlora, son of Ismail Kemal. They travelled north to Fier, Berat, Elbasan and to Tirana, where they met Essad Pasha on 25 November. Essad Pasha received them cordially although he showed his displeasure at the presence of Et’hem bey, the son of his rival. From Durrës, De Veer and Thomson continued on to Shkodra where they arrived on 29 November to inspect the contingents of international troops there. In Ndërfushas, they met Prenk Bibë Doda (1858-1920), prestigious chief of the Catholic Mirdita region. After three weeks of travel and meetings with local leaders in the north and centre of Albania, De Veer and Thomson returned to Vlora on 9 December. The border to the south of Albania had not been fixed and Greek troops had occupied large swaths of the country, refusing to withdraw so long as Albania was not able to guarantee order. The International Control Commission therefore asked the two officers to set up a military corps to establish order in the south. The Dutch Government was duly contacted with a request for more officers. At the same time, De Veer and Thomson mustered an initial 1,000 men in Albania itself - mostly refugees in Vlora - and from Kosova and Shkodra. In its final form, the new Albanian gendarmerie would have 5,000 men at its disposal, of whom about 800 had received proper training. On 24 December 1913, Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands officially appointed De Veer as head of the new Albanian gendarmerie corps. In early January 1914, Albania was faced with an uprising of pro-Ottoman forces which were opposed to the increasing Western influence in the country. In November 1913, these forces, under the influence of the Young Turks, had offered the vacant Albanian throne to General Izzet Pasha (1864-1937), the Turkish War Minister who was of Albanian origin. The confusion which reigned throughout the land was furthered by Izzet Pasha in his ambitions to divide and rule, in order to gain the throne. To this end, he sent a Young Turkish officer of Albanian origin called Beqir Grebena, known in Turkish as Bekir aga Grebenali or Bekir Fikri effendi, from Macedonia to Albania to stir up trouble and attempt to overthrow the provisional government in a coup d’état. In Shkodra, Grebena won over the Muslim community who felt disadvantaged by the Austro- Hungarian Kultusprotektorat, and in Durrës he managed to gain the confidence of Essad Pasha for a time. At the end of the year, in support of Grebena, the Young Turks sent 375 soldiers to Vlora, in civilian disguise, many of whom on board the Austrian steamer Meran. Syreja bey Vlora, however, caught wind of the undertaking and informed the International Control Commission without delay. Concerned at the thought of Turkish troops landing in Vlora, the ICC gave the Dutch officers full powers to act as they saw fit. On 6 January 1914, Thomson and De Veer immediately incorporated the local police into the new gendarmerie, which had been originally designed to take control of the south, and seized the telegraph and customs offices. When the Meran arrived in Vlora, they managed to capture and disarm the 19 officers and sent the 161 soldiers via Trieste back to Istanbul. Beqir Grebena was sentenced to death. At the same time, Essad Pasha, who was the only person in Albania to have a self-contained army of his own, strove to grab as much of the country as he could. On 9 January, his men tried to take Elbasan, but they were repulsed by the governor of the town, Akif Pasha Biçaku, also known as Aqif Pasha Elbasani. In his memorandum on Albania, published in August 1917, Prince Wied noted that “Essad Pasha and Ismail Kemal bey were at loggerheads and were plotting against one another in every possible way. Essad, who was by far the more important and powerful of the two, was endeavouring to expand his rule southwards to Elbasan. Using gifts and promises, he was cunningly able to extend his influence and that of his followers and relatives. He never openly opposed the International Commission, but rather slithered around it like an eel, constantly affirming his loyalty and claiming that he was ever ready to serve Europe and his new sovereign. Even at that time, the reports on his behaviour from the International Commission gave rise to suspicions that he was double dealing and only had the expansion of his power in mind. The influence of Ismail Kemal in the south was in constant decline. He lacked requisite military backing, as opposed to Essad who could rely both on the troops he had withdrawn from Shkodra and on fresh forces... There was no finance administration serving the interests of the country. Essad Pasha had his hands on the customs duties in Durrës, and Ismail Kemal bey on the customs revenues in Vlora. The two had thus put the country’s main sources of income to the service of their own personal needs. Ismail Kemal devoted a portion of the customs revenue to caring for the refugees and to the creation of a new gendarmerie corps, but Essad Pasha refused categorically to devote any public monies he had collected to these two expenditures, which the country so needed at the time. The Dutch officers who, in lieu of the Swedish officers originally foreseen, had been entrusted with the task of building up an international gendarmerie and who were devoting much energy and enthusiasm to this goal, got no support whatsoever from Essad Pasha in central Albania. He only created difficulties for them. He hindered their work from start to finish, making it clear that he already had a good Albanian gendarmerie. The south of Albania was a particular problem. Greece had still not evacuated the occupied Albanian territories. Numerous bands (komitadji) led by former Greek officers, no doubt (though not proven) supported by the Greek Government, were working towards fomenting uprisings and chaos in the region. In the course of its activities, the International Commission recognised that the elimination of these two powerful figures, Essad Pasha and Ismail Kemal bey, was an essential prerequisite to bringing peace and quiet to Albania and to enabling the new sovereign to ascend the throne. They recognised that the time was ripe to do away with Essad Pasha and Ismail Kemal bey because, in their view, the former had become too big for his boots and the latter was responsible for serious mismanagement. This view was strengthened by their involvement in the failed plot of the Young Turks which had endeavoured to install the Turkish General Izzet Pasha as ruler of Albania. The International Commission succeeded in persuading Ismail Kemal bey to resign from his position as president of the “provisional government,” for which he was eminently unsuited, but Essad Pasha continued to rule unimpeded as Head of the Executive of the Senate for Central Albania.” (1) Ismail Kemal bey Vlora was forced to leave Albania at the demand of the International Control Commission, but the Commission did not have enough authority to force Essad to do the same. Essad thus stayed put and only agreed to give up government if he were allowed to lead the Albanian deputation travelling to Germany in February 1914 to offer the Albanian throne to Prince Wied. On 23 February 1914, the rest of the Dutch officers arrived in Vlora, two weeks before the arrival of the Prince. They were first lieutenant Gerard Mallinckrodt, who became Thomson’s adjutant; the captains Wouter De Waal, Hugo Verhulst, Henri Kroon, Joan Snellen van Vollenhoven, Lucas Roelfsema and Johan Sluys; and the first lieutenants Carel De Iongh, Jetze Doorman, Jan Fabius, Julius Sonne, Hendrik Reimers and Jan Sar. Interestingly enough, part of the equipment which each received for his tour of duty was a camera. The contingent was completed by the health officer Tiddo Reddingius, a medical orderly sergeant J. van Vliet, and a civilian physician by the name of F. De Groot. Before the start of their mission to Albania, all of them had been promoted by one rank. The Dutch officers were swiftly distributed throughout the country. Sluys, Roelfsema and Sar were sent to Durrës, Kroon and Fabius to Shkodra, Snellen van Vollenhoven and Doorman to Korça, Verhulst and Reimers to Elbasan, De Waal and Sonne to Gjirokastra, and De Iongh remained with De Veer in Vlora. Chaos reigned in southern Albania and Epirus in the first half of 1914. Many of the Greeks, who made up about one-fifth of the population there, demanded unification with Greece. Greek troops had occupied Gjirokastra and Korça during the second Balkan War and, despite international admonition, had been refusing to withdraw up until February, when Austria-Hungary threatened to use force against them. In Gjirokastra, a provisional (Greek) government for Northern Epirus was set up, which was supported politically and militarily by Jorgios Christaki Zographos, the governor of Epirus and Greek minister of foreign affairs (1912-1915). The Greek army became more and more actively involved in supporting groups of armed guerillas and bandits, and by mid-April 1914, Greek forces had seized territory up to a line running from Himara to Përmet and Leskovik. The meagre forces of the Dutch officers were hopelessly outnumbered. In March 1914, soon after his arrival in Albania, Prince Wied appointed Thomson as general commissioner for the south. This appointment was much to the relief of De Veer who wanted to be rid of the temperamental Thomson. On 10 March, Thomson arrived in Corfu to negotiate with Greek forces, largely overstepping his mandate. Soon thereafter, on 6 April, Wied issued a decree for the conscription of all Albanian men aged 20 and 21. The Italian War Minister encouraged the Prince to march on Gjirokastra, assuring him of Italian support. The situation in the south of the country continued to be difficult. In mid-May, in an attempt to regain control of Gjirokastra, De Waal and his men, assisted by a corps of Albanian volunteers under Çerçiz Topulli, reached the Drino river and heard firing at the nearby Orthodox monastery of Kodra, near Tepelena. A terrible scene was discovered - the bodies of 218 old people, women and children who had been massacred by Greek forces. Some of the victims, Albanian Orthodox Christians, had been crucified, and others hacked to pieces. General De Veer reported to the ICC about the tragic event on 10 May: “South of the village of Kodra (Hormova), I found a little church which was undoubtedly used as a prison. In the interior the walls and the floor were washed in blood, everywhere were caps and clothing soaked in blood. The doctor, member of the Commission of Investigation, himself saw human brains. At the altar we found a human heart which was still bleeding. A hundred and ninety-five bodies were dug out because the ditch they were thrown in was too shallow, so as to bury them in deeper graves; all the bodies were without heads.” In the House of Commons in London, Aubrey Herbert (1880-1923) spoke passionately about the massacre, but Western public opinion had had enough of Balkan atrocities and there was little reaction. De Waal himself tried to storm Gjirokastra on 12 May with the help of a volunteer corps under Sali Butka (1857-1938), but was cut off by Greek troops under General Papoulias. A political agreement, the Disposition of Corfu, was reached on 17 May 1914, under which Northern Epirus would remain part of Albania, but would be under the control of the International Control Commission. The parliament of (Greek) Northern Epirus, however, refused to ratify the agreement, and the fighting continued well into the summer when, on 8 July, Korça fell to Greek troops under General George Tsontos Vardhas. Despite the arrival of Wied in Durrës, power in central Albania was firmly in the hands of Essad Pasha who had somehow managed to have himself appointed by Wied as war minister. As such, he was bound to come into conflict with the Dutch military mission which commanded the only officially armed troops in the country. Essad Pasha had promised to muster 20,000 reservists to march against the Greeks, but being himself in close contact with Greek rebel leaders, he did not keep his word. In early May 1914, Essad Pasha withdrew discreetly to his country estate near Tirana, and soon thereafter rumours spread of an armed rebellion in Shijak and Kruja. It was obvious to Wied and the Dutch officers that Essad Pasha had his hand in the unrest. Machine guns and mountain guns were delivered to Durrës from Austria to help defend the town, and Essad Pasha, who turned up on 18 May, was intent on getting his fingers on them to hand them over to the Italian military attachés, Muricchio and Moltedo. Johan Sluys, not trusting the Italians, insisted the cannons be manned by the officers Klingspor and Tomjenovic who had been seconded with them to train the men how to operate them. Essad Pasha demanded an audience with Prince Wied, whom he pressured to remove Major Sluys. As a result, the command of the military corps in Durrës was transferred for a time to Roelfsema. Rumours spread that Essad Pasha was housing 200 men and ammunition in his house in Durrës to prepare a coup d’état. On the morning of 19 May 1914, Sluys surrounded Essad Pasha’s house and tried to disarm his guards. When Klingspor fired a cannon shot, destroying part of Essad’s roof, and then another which burst into Essad’s bedroom, the unscrupulous war minister gave up and surrendered. Wied had his minister interned on the Austro-Hungarian warship Szigetvar which was anchored in the bay of Durrës. De Veer and Thomson arrived the next day from Vlora with proof, in the form of coded telegrams, of Essad Pasha’s treachery and collusion with the Italians. The Italian ambassador Baron Carlo Alberto Aliotti, however, persuaded Wied not to press charges and to exile Essad Pasha to Italy, where the latter was received as a martyr for the Italian cause. Essad Pasha was gone, but unrest in central Albania continued. The region around Shijak, between Durrës and Tirana, had been settled in part by Bosnian Muslims following the Austrian occupation of Bosnia in 1878. These people were uneasy about the fall of their Muslim Ottoman Empire and were wary of the Prince from the Christian West who had been imposed upon their country. Whatever the reason was for the uprising in Shijak and Kavaja that began on 17 May 1914 (the exiled Essad Pasha may have been a major figure behind the scenes), it constituted a direct threat to the administration of Wied in nearby Durrës. General De Veer gave Roelfsema orders to take Rrashbull, an elevation a few kilometres from Durrës and strategically important for its defence. Roelfsema and his men, mostly volunteers from Kosova under their leader Isa Boletini (1864-1916), took the hill on 20 May and met with no resistance. Plundering ensued and, fearful of a reaction, Roelfsema withdrew his forces. The small Dutch gendarmerie was no match for the large rebel forces which were converging on Durrës. The situation improved, however, when a ship arrived from the north with 150 volunteers from Catholic Mirdita and the northern mountains under Simon Doda, nephew of Prenk Bibë Doda. In order to secure military assistance, the Prince had made Prenk the new foreign minister of the country. On 22 May 1914, Jan Sar took the new troops under his command with 65 of his own gendarmes and set off in the direction of Tirana with an expeditionary force to establish order. On 23 May, they passed Rrashbull and engaged the Muslim rebels. The volunteer forces from the north, however, refused to attack the rebels because a general besa (cease-fire) had been agreed on the occasion of Wied’s accession to the throne. When they abandoned ranks and fled, Sar and forty of his men were surrounded and captured. Edith Durham later wrote of this incident: “A party of armed men, led by one of the Dutch officers, went to parley with the insurgents, and took a machine gun. Unluckily, Captain Sar was ignorant of local customs. He and his party were unduly nervous, for when an Albanian has given his besa (peace oath), he keeps it. Alarmed unnecessarily, he ordered his men to fire at a group of three armed men. One escaped, fled to Shijak and spread the alarm that the Prince had begun to massacre Moslems. A number of people rushed to aid the Shijak men, and a fight took place.” (2) When news reached Durrës of the capture of Sar, Dutch forces prepared an expedition to free him, but the rebels had captured Rrashbull and were already firing on Durrës with their light weapons. Roelfsema advanced with a unit, but was surrounded and taken prisoner, too. Panic broke out in Durrës, and the royal family sought refuge on an Italian vessel which was anchored in the bay. Ambassador Aliotti had persuaded Wied to take his family to safety there, and once they were on board, he ordered the captain of the ship to sail farther away from the coastline, thus preventing Wied from returning to land. This ‘flight’ severely damaged Wied’s reputation among the Albanians. The rebels released Jan Sar that evening and sent him to Durrës to present their demands, among which were a total amnesty and the restoration of the sultan. Wied appointed Colonel Thomson as commander of Durrës and, as there was no more war minister, as “directeur de la force armée.” Thomson was thus the prince’s principal military advisor. De Veer begrudgingly acceded and withdrew to Vlora on 4 June, subsequently returning to Holland. The newly created Principality of Albania had in reality now been reduced to a modest few kilometres of territory in and around Durrës. Thomson began constructing defence fortifications to protect the town, and brought all native and foreign fighters in Durrës under his strict control. An artillery unit was set up under Captain Fabius, who had returned from Shkodra, which had been occupied by international troops. The Italians were now secretly supporting the rebels. Wied described the situation at the time as follows: “The first days of June brought irrefutable proof of the long-held suspicion that the Italians were colluding with the rebels. On my vehement objection, the Italian ambassador Aliotti suspended his daily automobile trips to the rebels. Instead of this, however, we now observed secret flashing lights used by the Italians to communicate with the rebels. Thomson finally managed to catch three Italians in the act (Captain Muricchio, Captain Moltedo and the mysterious Professor Chinigo). Documents incriminating them were also found when they were searched. There were great problems with Italy because the capitulations were said to have been infringed upon when the Italian mission was entered by force to arrest them. Pointing to the capitulation law, Aliotti demanded that those under arrest be released, and released they were. Thomson, however, repeatedly rejected Aliotti’s other demand to retract publicly the newspaper reports that the Italians had been exchanging signals with the rebels and had been in continuous personal contact with them, insisting that the demand was wrong and that complying with it would be incompatible with his honour as an officer: (3) “Volontiers je donnerais ma vie au Roi, mais jamais mon honneur.” Aliotti now demanded that Thomson be sent back to Holland, thus depriving the city of Durrës of an industrious and energetic protector. This controversy came to a tragic end soon thereafter with the death of Thomson, which occurred on 15 June 1914 during a fierce rebel attack.” That day, the rebels had stormed and taken Rrashbull, and two days later they were preparing to attack Durrës. Jan Fabius, described by the Prince’s personal secretary, Duncan Heaton-Armstrong (1886-1969), as the most reckless and dashing of the Dutch officers, was on guard at the time and woke the defendants of the town with a cannon shot early on the morning of 17 June. Sar was sent to hold the hills to the north of town, and Roelfsema commanded the trenches to the west, where the brunt of the attack was to occur. Thomson inspected the artillery unit and joined Roelfsema near the petrol dump, less than three hundred metres from the enemy line. At the very start of the attack, Thomson was hit in the chest and died of his wounds within a few minutes. Whether, as rumoured, an Italian sniper was behind his death will never be known for certain. Prince Wied had, at any rate, lost his best man, but the defences of the town withstood the onslaught. On the next day, Thomson was laid to rest in a widely attended funeral on 16 June 1914. Even a number of rebels, in compliance with Albanian tradition and chivalry, made their way into town to attend the solemn occasion. In early July, Thomson’s body was returned to Amsterdam aboard the cruiser Noord-Brabant and, after a lying-in-state there, the much-lauded hero was buried in Groningen on 18 July 1914. The political situation was not much better for the Dutch officers in the other parts of the country. Verhulst had endeavoured to reach Tirana from Elbasan, but was taken captive. Reimers, too, was taken prisoner in Elbasan. De Iongh in Fier hoped to make use of the men of the influential Vlora family and of the landowning Vrioni family in Berat, but Aziz Pasha Vrioni preferred to retain his fighters to defend the region from the Greeks. De Iongh set out across the Seman river but only managed to hold out in Fier for three weeks. On 17 June, Major Kroon, who had arrived from Lezha to succeed Thomson, attacked Rrashbull once more, but was unsuccessful. The situation was so desperate that on 21 June 1914, Akif Pasha Biçaku sought a cease-fire with the Muslim rebels who were led by the Melami dervish, Haxhi Qamili; the mufti of Tirana, Musa Qazimi; the sheikh of Shijak, Hamdi Rubejka; Mustafa Ndroqi; and the one-time Turkish officer, Qamil Haxhi Fejza of Elbasan. The Dutch officers strongly disapproved and declared that they would henceforth leave the military to others and would devote themselves to the original purpose of their mission, which was organizing the gendarmerie. Events in Albania were, however, soon overshadowed by the assassination of Austro-Hungarian Archduke Franz Ferdinand (1863-1914) in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914 and the subsequent outbreak of World War I. The Dutch officers in Albania were gradually replaced by a volunteer corps of ca. 150 German and Austrian officers who arrived in Durrës on 4 July, organized by the Austrian sculptor Gustav Gurschner (1873-1970), who had designed Prince Wied’s uniforms and medals, and by detachments of Romanian volunteers who arrived in Durrës on 7 and 17 July. Berat fell to the rebels on 12 July and Vlora was occupied without a struggle on 21 August. By mid-summer, at any rate, with the fall of most of central Albania, public opinion in the Netherlands had it that the continued presence of the Dutch military mission in Albania would only result in a further loss of life, and General De Veer was pressed to tender his formal resignation and that of his men. This was done officially on 27 July 1914, one day before Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. On 4 August, most of the officers departed and returned to the Netherlands as quickly as they could; although, due to the war situation, some of them ran into substantial difficulties on their journey. Verhulst and Reimers were released in Shijak on 19 September and departed for Holland the next day. The Dutch adventure in the Balkans was over. It had lasted less than one year. Robert Elsie (1) Wilhelm zu Wied, Denkschrift über Albanien, Berlin 1917, p. 12-13. (2) Edith Durham: Twenty Years of Balkan Tangle, London 1920, p. 265. (3) Wilhelm zu Wied, Denkschrift über Albanien, Berlin 1917, p. 21.

| Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact |