Albania 1916

Albanien 1916

Shqipëri 1916

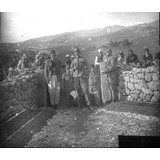

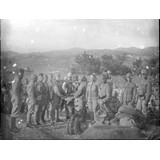

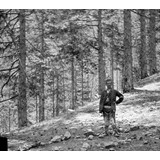

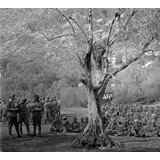

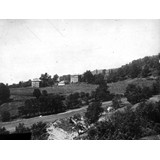

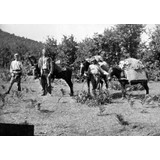

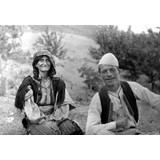

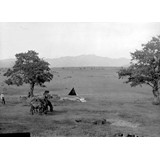

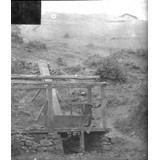

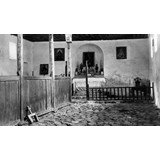

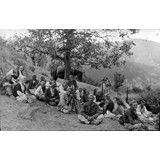

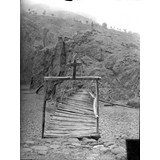

Photo Captions | Bildunterschriften | Titujt e fotove Report of the 1916 Expedition to Northern Albania Most of the photographs of Albania in the Max Lambertz collection were taken on his trip there in the summer of 1916, primarily in Mirdita. There include beautiful landscapes of Mirdita and northern Albania, and photos of the tribesmen in their traditional environment. The photographs of the Lambertz Collection, first published in the album “Writing in Light: Early Photography of Albania and the Southwestern Balkans,” Prishtina 2007, are now archived in the Bildarchiv of the Austrian National Library in Vienna (www.bildarchiv.at) to whom we are grateful for permission to make them available here. Fortunately, for the identification of the photographs, there exists a written report which Lambertz published of his journey to Mirdita that year. This “Report on my Linguistic Studies in Albania from Mid May to the End of August 1916" was published in Vienna by the Imperial Academy of Sciences. Here is a translation of the text of the report, excluding the material of purely linguistic interest. In the spring of 1916, the Balkan Commission of the Imperial Academy of Sciences in Vienna asked me to take part in a Balkan expedition organized by the Imperial Academy of Sciences in conjunction with the Imperial and Royal Ministry for Education and Teaching and the Office of the Imperial and Royal Treasurer with the purpose of carrying out linguistic and folklore research in Albania. I set off from Vienna on 19 May in the company of the art historian and epigraphist of our expedition. After a short stay in Sarajevo which was used for research at the Provincial Museum, we travelled to Kotor and up the Lovčen to Cetinje and Podgorica. Here I left my travelling companions and set off for the Gruda tribe. This Albanian tribe, which is geographically the farthest away, inhabits the mountains to the east of Podgorica in the valley of the Cem (Cijevna), in the villages of Dinosha, Pikala, Prifti, Lofka, Bozhaj and Selishta. Baron Nopcsa travelled through this area in the summer of 1907 to reach the Shala and Kelmendi. On 28 May, I arrived in Prifti, a settlement between Pikala and Lofka where the parish priest of Gruda lives. It is not a real village, but does have a fine, new parsonage built with funds from our monarchy, and a church, which is a few minutes away. The name of the settlement means “the priest”. Like Prifti, many Albanian toponyms derive their origins from the name or title of the first settler. The toponym Domgjoni, for instance, which occurs several times in northern Albania denotes the place where a parish priest named Gjon settled, around which a village grew. The numerous toponyms in -aj are equivalent to our German toponyms in -ing, -ingen, -ungen. The present parish priest of Gruda is the very kind Franciscan, Bonaventura Gjeçaj, an Albanian by birth whom his parishioners call Pater Bona, evincing the typically Albanian dislike for long names. He and the First Lieutenant of the Fusiliers, Czuninka, who was administering Gruda at the time, gave me a hearty welcome. As such, I was able to carry out my research in the middle of Gruda without any difficulty because the inhabitants of the surrounding villages were wont to gathered in Prifti to attend church services, to receive their government allocations of maize and to settle legal disputes before the judge appointed by the commander. I conversed with them to listen in on their dialect and, once they had overcome their initial mistrust and were convinced that I had not come to build factories in their valley, they sang songs to me on the lahuta, which I wrote down... After several days there, I was able to get a grasp of the dialect of the likeable Gruda tribe. I would like to have stayed longer in the beautiful Cem valley, but I had to get to Shkodra, the intellectual centre of northern Albania. I thus took the road back to Podgorica and, since my travelling companions were scattered throughout Montenegro, each absorbed in his own field of studies, I continued on to Shkodra by myself... When the other participants in the expedition arrived in Shkodra, I joined them on their journey southwards. We travelled to Lezha, from where I made a side trip to Vela with Dr. Kidrić. From Lezha, I travelled with Dr. Buschbeck and a German gentleman across the Fusha e Molungut to the old abbey of Rubik, now inhabited by the Franciscans, the history of which has been recorded by Milan von Šufflay in the informative volume Illyrisch-albanische Forschungen (Illyro-Albanian Research) recently edited by Ludwig von Thallóczy. We spent Whitsuntide in Rubik. From the imposing and hospitable abbey situated on a mountain with a view into the distance, we carried on down the valley of the Fan river to where it flows into the Mat and, crossing the Mat, we reached Milot. I noticed on this part of the journey that the dialect of Mirdita is also spoken in the Malësia e Lezhës (mountains of Lezha) and stretches from Lezha to the Adriatic. From Milot we continued via Mamurras to the old residence of Scanderbeg, the splendidly situated settlement of Kruja with its natural springs. The dialect of Kruja is not entirely the same as the speech of Durrës and Elbasan described by Weigand and should be studied and recorded on its own. Unfortunately I had no time for this. From Kruja we rode through fertile lowlands covered in olive orchards to the beautifully situated town of the Toptanis, Tirana, which made a tremendous impression on us with its sumptuous and friendly Muslim homes and fair gardens hidden idyllically behind high, yet inconspicuous yellow walls... In Tirana I left my travelling companions so as to have more time for my principal objective and travelled back to Shkodra, via Durrës and Lezha, from which I visited Shëngjin this time. I spent the next three weeks in Shkodra continuing my research into the dialect of Mirdita with Marka Gjoka and other men of Mirdita, and studied Albanian children’s songs with the assistance of the aforementioned Pater Vinçenc Prennushi. On several occasions I visited school classes which are conducted according to Austrian curricula both at the Franciscan school and the public school. The schoolboys, most of whom were bright and talented, are well versed in arithmetic, geometry and Albanian grammar. The Franciscans and the public school also teach German with some success, such that many of the young boys are able to serve our troops as interpreters. I recorded thirteen folktales in Shkodra directly from the mouths of skilled informants. That I was not able to record more than this was due to the fact I did not have enough time to conduct private conversations with the natives and get to know them personally, something which is particularly important in this field of research. The other participants of the expedition had returned to Shkodra by this time and I decided to adjust my plans for travelling to Mirdita in line with their objective of travelling through northern Albania to Gjakova, thus hoping to reach Mirdita after a detour through northern Albania. We left Shkodra at the beginning of July and journeyed up the valley of the Kir river past Drisht and Prekal into Shoshi territory. Mark Lulashi of Shoshi served as our guide and proved to be a good informant for the dialect of Shoshi. This dialect is characterized by the pronunciation ofk’ as ts and of g’ as dz. I also recorded songs in the dialect of Shoshi. From the Qafa e Gurakuqit (Gurakuqi Pass), our journey led us through Shoshi down into the valley of the Lumi i Shalës (Shala river), from which, leaving Abat to our left, we climbed up to the Qafa e Agrit (Agri Pass) which constitutes the frontier between Shala and Merturi. From here we climbed over Palç to Kotec and reached the Drin valley before Kotec. The trip had offered a wealth of splendid views from Drisht onwards, with imposing panoramas of high mountains, gentle valley scenes in Shoshi and sombre landscapes in Shala, but, entering the Drin valley which meanders from here through the mountains of Merturi, we enjoyed spectacularly beautiful scenery. From Kotec on the Drin we continued up to Raja, the last settlement in Merturi. This parish, where Pater Gjon lives a lonely existence, is situated where the Valbona flows into the Drin. Up the valley of the Valbona is the territory of the Muslim Krasniqi tribe, which does not at all merit the bad reputation it has as hostile and savage. I got to know a number of old Krasniqi men in Gegëhysen and found them to be intelligent folk who enjoy a good joke and yet who are dignified Muslims. Their dialect belongs to the Gjakova group. I left my three travelling companions in Valbona who continued northeastwards, whereas I journeyed southwards, returning to Raja at the entrance of the valley. There, I met Beqir Nou and Kol Marku who both proved to be willing informants for their dialect on the border of Merturi, where in absolute mountain solitude, the charming Valbona, teeming with fish, flows into the Drin, and the Krasniqi, Gashi and Thaqi tribes encounter the Merturi... I forded the Valbona below Raja and then crossed the Drin in an extremely primitive double dugout. I was now on the land of Fierza in the tribal territory of the Thaqi and, for a while, I travelled the same route which Karl Steinmetz had taken in August 1903 and described in his book Eine Reise durch die Hochländergaue Oberalbaniens (A Journey through the Highland Reaches of Upper Albania), which was the first volume published by Patsch in his series Schriften zur Kunde der Balkanhalbinsel (Writings for a Knowledge of the Balkan Peninsula). But he did the journey in the reverse direction, from south to north. I travelled southwards from Fierza through fair virgin forest with tall oak trees to the charming valley of Iballja, which is surrounded by subalpine mountains. The ferryman who took me across the Drin was a good guide and source for the dialect of the Thaqis which, like that of Raja, has an intermediary position between Gjakova and Mirdita. In Iballja I left the route travelled by Steinmetz, who had come to Iballja from Kryezi, and set off on a westwardly trail over the Qafa e Çomorisë (Çomoria Pass). From here the trail plunges down to the Lumi i Sapaçit (Sapaç river) in Berisha and then climbs steeply up to the slopes of Krrab with its black forests to reach Qafa e Tmugut (Tmug Pass). From there it descends through oak forests to the fertile valley of Qelëza and rises to a level of 820 m. to reach the plateau of Puka. Along this route there are beautiful views to be had in a sweeping crescent to the north. There are eight ranges of mountains, one behind the other, and each of which in a different hue, from the green wooded hills to the grey, snow-covered giant of stone. From here, one has a view of all of northern Albania, right to the Northern Albanian Alps and Mount Shkëlzen. Up on the plateau, one can see that the Romans had a good eye, not only in Carnuntum in Austria, but also here in Epicaria (Puka), for choosing the finest and best sites for their fixed camps, from which they could control the whole region. Von Hahn and Baron Nopcsa both recognized that the hill on which present-day mosque is situated is unquestionably the site of a Roman fortification. Sufficient proof of this are the rectangular form of the hill, the evident remains of ancient walls fashioned of well- hewed stone, some of which have been set into the walls of the nearby armoury barracks, and lastly the minaret of the mosque, built almost entirely of Roman stone. From Puka, I initially travelled eastwards to Bicaj in the valley of the Greater Fan river and then for a whole day on precarious trails up above the Fan valley southwards to Kalivarja. From Bicaj onwards, I was in Mirdita and had once again joined the aforementioned route used by Steinmetz. The settlements which I passed through in Mirdita, in the bairak of Spaç, were Shmihija, Shkoza and Gojan. I left the valley of the Greater Fan in Kalivarja and climbed out of the verdant valley of the Lumi i Kalivares (Kalivarja river) past Mesul and the mountain pastures of Mushta to the Qafa e Lugjut (Lugj Pass) (1465 m.) on the southern flank of the Munella summit. I left the summit to my left, which Steinmetz was first to climb in 1903 and which the men of Mirdita used as a point of departure for their battles with Essad last year, and climbed, guided by Mark Deda of Domgjoni, through hours of wonderful beech forests in which one could see trenches and obstructions along the way from the recent fighting. We reached the mountain pastures of Domgjoni which conveyed to me, as did those of Mushta, a vivid impression of a typical Albanian bjeshka, and then descended into the valley of the Lesser Fan towards Domgjoni. There I said farewell to Mark Deda of whom I had made great use for my linguistic research. Travelling down the valley of the Lesser Fan, I took the trail past the parish of Fan and spent the night in a secret and hidden spot in the cliffs which is used as a gathering place for the chieftains of the bairak, and reached Orosh, the capital of Mirdita, by the next day. This finely situated residence of the Abbot of Mirdita has been described by several travellers already, notably by A. Degrand in his Souvenirs de la Haute-Albanie, 1901 (Memories of High Albania) and by K. Steinmetz in the above-mentioned work. Situated on a terrace of the mountain which forms the left bank of the Fan, half way up from the bottom of the valley, Orosh, with its splendid church visible from a distance on the southern side and with its spacious abbey, reminds one of our Maria-Taferl. On the opposite side is the village of Orosh which runs up a steep, tongue- shaped slope of the Holy Mountain (Mali i Shejtit). The abbot now lives in Shkodra and the abbey is the centre of a station command, of which I was the guest for several days. I used my time there to climb up to the village of Orosh on numerous occasions and visit the men of Mirdita in their kullas (stone towers) and gather information on their dialect by making vocabulary lists and by recording conversations. I noted with satisfaction that my Mirdita informants in Shkodra had taught me a pure and unadulterated form of the dialect. I was delighted at an opportunity to visit the neighbouring region of Lura when a police patrol in Orosh was to be sent there and the commanding officer invited me to go with them. It is the homeland of one of the most notorious Albanian tribes, known for its savagery and hostility to outsiders. I knew about it from the descriptions made by K. Steinmetz in his book Von der Adria zum schwarzen Drin (From the Adriatic to the Black Drin). Lura is a one day’s march from Orosh. The trail leads left from the Mali i Shejtit over the broad, wooded expanses of the plateau of Fusha e Shejtit (Holy Plateau), on the eastern side of which, where we took our noonday rest, one could see several sod huts and a lot of empty tins of food with Cyrillic inscriptions lying around, the remnants of a Serb encampment from the days of the flight of the vanquished Serb army through Albania. From here, the trail descends into the Malla valley and then rises to the left through a wooded gorge to Lura e Epër, which is splendidly situated in a valley at an altitude of 1100 m. Its location reminded me of our highest Tyrolian towns, Gurgl and Vent. The 19th Imperial Fusilier Battalion happened to be in Lura e Epër at the time, having undertaken an expedition there. Its commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Gustav Broser, received me hospitably and, since he had to continue on from Lura to the neighbouring settlements of Kthella and Selita as a court judge, he asked me whether I might not come with him and put my knowledge of the native language to the service of the expedition. I willingly accepted his proposal, not only because I was happy to be of service, but also because the trip provided me with a welcome opportunity to get to know the tribe and the language of Kthella. When the trial in Lura was over, I continued on with the 19th Fusilier Battalion via Orosh and Kthella e Epër to Selita where we camped on the Qafa e Kishës (Church Pass) between the church and parsonage in the midst of this bellicose tribe. What I experienced in my ten days with the 19th Fusilier Battalion, working closely with the forthcoming officers of these troops, in one of the roughest areas of Albania, belongs more to a chapter in the political history of Albania in these stormy times than to a scholarly report submitted to a learned body. Suffice it to say that both the Muslim Luras and the Catholic Kthellas, who are by no means any better, had to be taught that the “good old days” in Albania were over and that European civilization, represented by the Austro-Hungarian army, was now knocking on the door of Albania, which up to now has remained resolutely closed to all cultural and ethical advancement. Having fulfilled my duties as a “court interpreter” and having learnt something of the dialect of the tribes, which is quite similar to that of Mirdita, I said farewell to the gentlemen of the battalion and returned to Shkodra via Orosh, Blinisht, Ungrej, Vig and Vau i Dejës. After a short stay there, I set off on my journey homewards. [Extract from: Maximilian Lambertz: Report on my Linguistic Studies in Albania from Mid May to the End of August 1916 [Bericht über meine linguistische Studien in Albanien vom Mitte Mai bis Ende August 1916]. in: Anzeiger der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien, Phil.- hist. Kl., Vienna, 53 (1916) no. XX, p. 122-146. Translated from the German by Robert Elsie.] Bericht zur Reise in Nordalbanien, 1916 Die meisten Albanien-Fotographien von Max Lambertz wurden auf seiner im Auftrag der Balkankommission der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien unternommenen Reise des Jahres 1916. Unter ihnen sind schöne Aufnahmen von Mirdita und Nordalbanien sowie Fotos albanischer Stammesmitgliedern in ihre traditionellen Trachten. Die hiesige Sammlung wurde zum ersten Mal in dem Fotoalbum “Writing in Light: Early Photograph of Albania and the Southwestern Balkans”, Prishtina 2007, veröffentlicht. Der Nachlass der Lambertz-Sammlung befindet sich im Bildarchiv der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek in Wien (www.bildarchiv.at), dem wir für die Erlaubnis zur Verwendung der Bilder dankbar sind. Zum Glück besteht für die Identifizierung der Photographien auch ein Bericht über die Reise. Dieser in Wien erschienener “Bericht über meine linguistische Studien in Albanien vom Mitte Mai bis Ende August 1916" wird hier wiedergegeben mit Ausnahme des Materials von rein sprachwissenschaftlichem Interesse. Im Frühjahr 1916 betraute mich die Balkankommission der kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien mit der Aufgabe, an der von der kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften im Einvernehmen mit dem k. k. Ministerium für Kultus und Unterricht und dem k. u. k. Oberstkämmereramte veranstalteten Balkanexpedition teilzunehmen, um in Albanien linguistische und folkloristische Studien zu betreiben. Am 19. Mai brach ich in Gesellschaft des Kunsthistorikers und des Epigraphikers unserer Expedition von Wien auf. Nach kurzem Aufenthalt in Sarajevo, der zum Studium des Landesmuseums benützt wurde, ging die Reise über Kotor und den Lovčen nach Cetinje und Podgorica. Hier trennte ich mich von meinen Reisegefährten und begab mich zu dem Stamme der Gruda. Dieser äußerste Albanerstamm haust in den Bergen östlich von Podgorica im Cemtale in den Dörfern Dinoši, Pikala, Prifti, Lofka, Božaj und Selište. Baron Nopcsa hat das Gebiet im Sommer 1907 durchgewandert, um zu den Šala und Klementi zu gelangen. Am 28. Mai langte ich in Prifti an, der zwischen Pikala und Lofka gelegenen Siedlung des Pfarrers von Gruda. Diese ist heute noch kein Dorf, sondern besteht nur aus dem stattlichen, mit dem Gelde unserer Monarchie erbauten, neuen Pfarrhause und dem einige Minuten davon entfernten Kirchlein. Der Name der Siedlung bedeutet “der Priester”. Wie Prifti verdanken sehr viele albanische Ortsnamen ihre Entstehung dem Namen oder Titel des ersten Siedlers. Der in Nordalbanien mehrfach vertretene Ortsname Domgjoni zum Beispiel bezeichnet die Ansiedlung des Pfarrers Gjon, um die sich ein Dorf bildete. Die vielen Ortsnamen auf -ai sind durchaus Sippennamen, die unseren Namen auf - ing, -ingen, -ungen entsprechen. Pfarrer von Gruda ist jetzt der liebenswürdige Franziskanerpater Bonaventura Gječaj, ein gebürtiger Albaner, den seine Pfarrkinder mit dem den Albanern eigentümlichen Abscheu von langen Eigennamen P. Bona nennen. Er sowie der Grenzjägeroberleutnant Czuninka, der damals Gruda verwaltete, nahmen mich mit herzlichster Gastfreundschaft auf. So konnte ich dort im Zentrum Grudas meinen Studien bequem nachgehen; denn die Einwohner der zugehörigen Dörfer versammelten sich in Prifti sowohl des Gottesdienstes wegen, wie auch um ihren ärarischen Kukuruz zu fassen und um ihre Rechtsstreitigkeiten vor dem Richterstuhle des Kommandanten auszutragen. Ich führte mit ihnen Gespräche, um ihren Dialekt zu hören, und nachdem sie ihr erstes Mißtrauen überwunden und die Überzeugung gewonnen hatten, daß ich nicht gekommen sei, in ihrem Tale Fabriken zu gründen, sangen sie mir auch zur Lahuta Lieder, die ich nachschrieb... In mehrtägigem Aufenthalte konnte ich mir einen Einblick in die Mundart des sympathischen Kriegerstammes der Gruda verschaffen. Gern wäre ich noch länger im schönen Cemtale geblieben, aber es zog mich nach Schkodra, dem geistigen Zentrum Nordalbaniens. Ich nahm also den Weg wieder zurück nach Podgorica, und da meine Reisgefährten sich, jeder seinen speziellen Studien nachgehend, in Montenegro zerstreut hatten, machte ich mich allein auf den Weg nach Schkodra... Nachdem sich auch die anderen Teilnehmer an der Expedition in Schkodra eingefunden hatten, schloß ich mich ihrer Reise nach dem Süden an. Diese ging nach Lesch [Lezha], von wo ich mit Dr. Kidrić einen Abstecher nach Velja machte. Mit Dr. Buschbeck und einem reichdeutschen Herrn begab ich mich von Lesch aus über die Fuša Malungut [Fusha e Molungut] nach dem jetzt von Franziskanern bewohnten alten Kloster Rubigu, dessen Geschichte L. v. Sufflay in den von Thallóczy eben herausgegebenen inhaltsreichen Illyrisch-albanischen Forschungenbehandelt. In Rubigu verbrachten wir den Pfingstsonntag. Von dem imposant auf einem Berge gelegenen, weit ins Land blickenden, gastlichen Stifte zogen wir das Tal des Fan abwärts bis zu seiner Mündung in den Mat und den Mat überschreitend nach Miloti. Ich stellte auf diesem Teil der Reise fest, daß der Dialekt der Mirdita auch in der Maltsija Lešs [Malësia e Lezhës] gesprochen wird und in Lesch bis an die Adria reicht. Von Miloti ging es über Mamuraš nach Skanderbegs alter Residenz, dem malerisch gelegenen Quellorte Kruja. Der Dialekt von Kruja deckt sich nicht ganz mit dem von Weigand beschriebenen von Durz [Durrës] und Elbasan, sondern müßte für sich studiert und aufgenommen werden, wozu mir diesmal die Zeit gebrach. Von Kruja ritten wir durch die fruchtbare, mit Ölbaumpflanzungen geschmückte Niederung nach der lieblich gelegenen Stadt der Toptanis Tirana, das mit seinen hinter hohen, unscheinbar gelben Mauern idyllisch versteckten anmutigen Gärten und prächtig-freundlichen Mohammedanerheimen auf uns einen tiefen Eindruck machte... In Tirana trennte ich mich von meinen Reisegefährten, um nicht zu viel Zeit meiner Hauptaufgabe zu entziehen, und begab mich über Durz und Lesch, von wo aus ich diesmal Schen Gjin [Shëngjin] besuchte, nach Schkodra zurück. In Schkodra hielt ich mich diesmal drei Wochen auf, setzte mit Marka Gjoka und anderen Mirditen mein Studium des mirditischen Dialekts fort und ließ mir im Verkehre mit dem schon genannten P. Vinzenz Prennushi, das Studium albanischer Kinderlieder angelegen sein. Einige Male besuchte ich auch den Schulunterricht, der bei den Franziskanern und in der Gemeindeschule nach österreichischen Unterrichtsplänen betrieben wird. Die zumeist mit leichter Auffassung begabten Knaben wissen im Rechnen und in der Geometrie, ebenso in albanischer Grammatik gut Bescheid. Auch Deutsch lehren die Franziskaner und die Gemeindeschule mit gutem Erfolg, so daß mancher der kleinen Jungen unseren Truppen als Dolmetsch zu dienen imstande ist. Aus dem Munde geschickter Märchenerzähler zeichnete ich in Schkodra dreizehn Märchen auf. Daß die Zahl nicht größer ist, lag an den Zeitumständen, die das gerade für diese Seite der Forschung notwendige friedlich-behagliche Zusammensitzen mit den Eingeborenen seltener ermöglichten. Unterdessen kehrten die anderen Teilnehmer an der Expedition nach Schkodra zurück, und ich beschloß, meinen Plan, in die Mirdita zu gehen, mit dem ihrigen, durch Nordalbanien nach Djakova [Gjakova] zu ziehen, zu vereinigen und auf dem Umweg über Nordalbanien nach Mirdita zu gelangen. Anfang Juli brachen wir von Schkodra auf und zogen durchs Kirital an Drišti vorbei über Prekalli ins Gebiet der Šoši. Als Wegführer diente uns bis Abbata Mark Lulaši aus Šoši, der mir unterwegs ein bequemer Gewährsmann für die Mundart von Šoši war. Diese zeichnet sich besonders durch die Aussprache von k’ als ts und von g’ als dz aus. Auch Lieder im Dialekt von Šoši zeichnete ich auf. Von der K’afa Gurikuk’ [Qafa e Gurikuqit] führte uns der Weg an Šoši vorbei hinab ins Tal des l’umi Šals [Lumi i Shalës], von dem aus wir, Abbata [Abat] links liegen lassend, zur K’afa Agrit [Qafa e Agrit] emporklommen, die die Grenze zwischen Šala und Merturi bildet. Von hier stiegen wir über Paltsa [Palç] ab nach Kotets zu und erreichten vor Kotets das Drintal. War die Tour schon von Drišti an überreich an landschaftlich prächtigen Bildern, imposanten Hochgebirgspanoramen, lieblichen Talbildern in Šoši und düster-trotzigen in Šala gewesen, so hatten wir beim Eintritt ins Drintal, das sich hier zwischen den Bergen von Merturi durchzwängt, Blicke von unbeschreiblicher Schönheit. Von Kotets am Drin aus stiegen wir nach Raja, dem letzten Orte der Merturi, empor. Es ist der Pfarrort an der Einmündung der Valbona in den Drin, wo P. Gjoni sein einsames Leben verbringt. Valbonatal einwärts haust schon der mohammedanische Stamm der Kraisnići [Krasniqi], der übrigens seinen bösen Ruf der Fremdenfeindlichkeit und Wildheit gar nicht verdient. Ich trat einigen alten Kraisnićis in Gegušen’ [Gegëhysen] näher und lernte sie als aufgeweckte, für Scherz empfängliche, allerdings sehr würdevolle Mohammedaner kennen. Ihr Dialekt gehört schon zu der Djakovagruppe. Im Valbonatal trennte ich mich von meinen drei Reisegefährten, die nach Nordosten zogen, während mich mein Weg nach Süden führte, und kehrte nach Raja am Eingang des Tales zurück. Dort fand ich in Beqir Nou und Kol Marku zwei willige Gewährsmänner für ihren Heimatsdialekt an der Grenze von Merturi, wo in weltentlegenster Bergeinsamkeit die liebliche, fischreiche Valbona in den Drin mündet und Kraisnići, Gači [Gashi] und Saši [Thaqi] mit Merturi zusammenstoßen... Unterhalb Rajas überschritt ich durch eine Furt die Valbona und setzte dann in einem urprimitiven Doppeleinbaum über den Drin. Damit war ich auf dem Boden von Firdha [Fierza] im Stamme Saši [Thaqi] und für eine Strecke Weges auf derselben Route, die K. Steinmetz im August 1903 begangen und in seiner Schrift Eine Reise durch die Hochländergaue Oberalbaniens, dem ersten Hefte der von Patsch herausgegebenen Schriften zur Kunde der Balkanhalbinsel, beschrieben hat. Doch machte er die Tour umgekehrt wie ich, von Süden nach Norden. Durch schönen Urwald von hohen Eichen ging es von Firdha südwärts in den lieblichen Kessel von Ibalja [Iballja], der von mittelhohen Bergen umgeben ist. Der Drinferge war mir Wegführer und sprachliche Quelle für den Dialekt von Saši, der wie jener von Raja eine Mittelstellung zwischen Djakova und Mirdita einnimmt. In Ibalja verließ ich Steinmetzens Route, der von Krüezi [Kryezi] nach Ibalja gekommen war, und zog den westlichen Weg über die K’afa Tšomorís [Qafa e Çomorisë]. Von dieser führt der Weg recht halsbrecherisch hinab zum Ljumi Sapaçit [Lumi i Sapaçit] in Beriša [Berisha], steigt hierauf steil an den Hängen des schwarzbewaldeten Krabi [Krrab] empor zur K’afa Tmugut [Qafa e Tmugut] und senkt sich dann abwärts durch Eichenwald in das fruchtbare Tal von Čelza [Qelëza], aus dem er bis zu 820 m. Seehöhe auf das Hochplateau von Puka emporklimmt. Auf dieser Strecke eröffnen sich schöne Panoramen im weiten Halbkreis nach Norden. Acht Kulissen von Bergen reihen sich hintereinander, jeder anders gefärbt, vom grünbewaldeten Hügel bis zum grauen schneebedeckten Steinriesen. Man übersieht ganz Nordalbanien bis an die Nordalbanischen Alpen und den Škeltsen [Shkëlzen]. Oben auf dem Hochplateau zeigt sich, daß die Römer wie bei uns in Carnuntum, so auch dort in Epicaria [Puka] mit scharfem Blick den besten und schönsten Platz, der die ganze Gegend beherrscht, für ihr festes Standlager auserlesen haben. Daß der mitten im Plateau gelegene heutige Moscheehügel fraglos der Platz des Römerkastells war, haben schon v. Hahn und Baron Nopcsa erkannt. Die quadratische Form des Hügels, die deutlich erkennbaren Reste der antiken Umfassungsmauer aus schön behauenen Steinen, von denen einige in die nahegelegene Magazinsbaracke eingemauert sind, schließlich das fast durchwegs aus römischen Architekturstücken erbaute Minaret der Moschee beweisen es zur Genüge. Von Puka zog ich zunächst ostwärts nach Bicaj im Tal des großen Fan und nun einen Tag lang auf recht bedenklichem Saumpfade hoch über dem Tal des Fan südwärts bis Kalivari [Kalivarja]. Von Bicaj an befand ich mich schon in Mirdita und war wieder auf die vorhin erwähnte Route Steinmetzens gestoßen. Mirditenorte des Bairaks Spači, die ich unterwegs berührte, waren Šmihija, Škoza [Shkoza], Gojani. In Kalivari verließ ich das Tal des großen Fan und erstieg aus dem grünen Tal des Ljumi Kalivarit über Mesul und die Alm von Mušta die K’afa Lug’ut (1465 m.) am Südfuß der Munelakuppe. Diese selbst, die Steinmetz als erster 1903 erstieg und von der aus die Mirditen im verflossenen Jahre ihre Kämpfe gegen Essad ausfochten, ließ ich links liegen und stieg, von Mark Deda aus Domgjoni geführt, durch stundenweite wunderbare Buchenwälder, in denen man noch auf Verschanzungen und Weghindernisse aus den Tagen jener Kämpfe stößt, über die Alm von Domgjoni, die mir wie die vorhin erwähnte von Mušta die lebendige Vorstellung einer albanischen bješka vermittelte, ins Tal des kleinen Fan nach Domgjoni ab. Dort entließ ich Mark Deda, den ich unterwegs für meine sprachlichen Zwecke ausgenützt hatte. Das Tal des kleinen Fan abwärts, nahm ich den Weg an der Pfarre Fani vorbei, übernachtete auf dem geheim gehaltenen und versteckt in einer Felswildnis gelegenen Thingplatze der Dorfältesten des Bairaks und langte am nächsten Tage in Oroschi [Orosh], dem Zentrum der Mirditen, an. Diese lieblich gelegene Residenz des Mirditenabtes ist schon von einigen Reisenden, besonders von A. Degrand in Souvenirs de la Haute-Albanie (1901) und von K. Steinmetz in seiner oben zitierten Schrift beschrieben worden. Auf einer Stufe des Berges, der das linke Fanufer dort bildet, in halber Höhe seines hinteren Abhanges hoch über der Talsohle gelegen, erinnert Orosch mit seiner stattlichen, nach Süden zu weithin sichtbaren Kirche und der geräumigen Abtei etwas an unser Maria-Taferl. Gegenüber klettert an einem zungenförmigen, steil ansteigenden Hange des hl. Berges, des Mali Šen’t [Mali i Shejtit], das Dorf Orosch empor. Der Abt wohnt jetzt in Schkodra, die Abtei ist Sitz eines Stationskommandos, als dessen Gast ich hier mehrtägigen Aufenthalt nahm. Diesen benützte ich, um mehrmals nach dem Dorfe Orosch emporzusteigen, dort die Mirditen in ihren Kullen aufzusuchen und mir durch Anlegung von Wortlisten und Aufzeichnung von Gesprächen einen Einblick in ihren Dialekt zu verschaffen. Ich stellte zu meiner Befriedigung fest, daß meine mirditischen Gewährsmänner in Schkodra mir ein reines und unverfälschtes Mirditisch übermittelt hatten. Als von Orosch eine Gendarmeriepatrouille nach dem benachbarten Gebiet der Lurja [Lura] abging und der sie kommandierende Offizier mich einlud, mitzukommen, ergriff ich mit Freuden die Gelegenheit, in das Gebiet jenes wegen seiner Wildheit und Fremdenfeindlichkeit verrufensten Albanerstammes zu kommen, der mir schon au den Schilderungen K. Steinmetzens in seinem Werk Von der Adria zum schwarzen Drin wohlbekannt war. In einem Tagesmarsch erreicht man von Orosch aus Lurja. Der Weg führt links vom Mali Šen’t über das weite, bewaldete Hochplateau der Fuša Šen’t, auf dessen östlichem Rande, wo wir Mittagsrast hielten, sich noch mehrere Erdhütten und zahlreiche umherliegende leere Konservenbüchsen mit cyrillischen Aufschriften als die Reste eines serbischen Lagers finden aus den Tagen der Flucht des geschlagenen serbischen Heeres durch Albanien. Von hier senkt sich der Weg ins Mallatal und steigt dann links durch einen waldigen Graben nach Lurja eper, das wunderschön 1100 m. hoch in einem Gebirgskessel liegt. Seine Lage erinnerte mich lebhaft an die unserer höchsten Tiroler Orte Gurgl und Vent. In Lurja eper weilte gerade das k. u. k. 19. Feldjägerbataillon, das dorthin eine Expedition unternommen hatte. Sein Kommandant, Herr Oberstleutnant Gustav Broser, nahm mich gastlich auf und da er von Lurja aus noch nach dem benachbarten Kseła [Kthella] und Selita ziehen mußte, um dort als Richter zu amtieren, richtete er an mich die Bitte, mitzukommen und meine Kenntnis der Landessprache in den Dienst der Expedition zu stellen. Gern ging ich auf diesen Vorschlag ein, weil es mich erstens freute, hier etwas nützen zu können, zweitens die Gelegenheit, Stamm und Sprache der Kseła kennen zu lernen, mir sehr willkommen war. Nachdem das Gericht in Lurja beendet war, zog ich also mit dem 19. Jägerbataillon über Oroschi und Kseła eper nach Selita, wo wir auf der K’afa Kišs [Qafa e Kishës] zwischen Kirche und Pfarrhaus im Mittelpunkte dieses unfriedsamen Stammes unser Zeltlager aufschlugen. Was ich in zehntägigem Zusammensein mit dem 19. Jägerbataillon, in emsiger Zusammenarbeit mit den liebenswürdigen Offizieren dieser Truppe in einem ungemütlichen Winkel Albaniens erlebte, gehört mehr in ein Kapitel der politischen Geschichte Albaniens in dieser sturmbewegten Zeit als in den wissenschaftlichen Bericht an eine gelehrte Körperschaft. Nur so viel sei gesagt, daß sowohl die mohammedanischen Lurjas, wie die nicht um ein Haar besseren katholischen Ksełas mit Nachdruck darauf aufmerksam gemacht werden mußten, daß die “guten alten” albanischen Zeiten vorbei seien, und daß in Gestalt des österreichisch-ungarischen Heeres die mitteleuropäische Zivilisation sich erlaube, an ihre bisher jedem Fortschritt in kultureller und ethischer Hinsicht verschlossenen Pforten anzupochen. Nachdem ich hier meine Aufgabe als “Gerichtsdolmetsch” erfüllt und nebenbei mich auch über die Mundart der Stämme orientiert hatte, die der von Mirdita ganz nahe steht, nahm ich von den Herren des Bataillons Abschied und kehrte über Oroschi, Bliništi, Ungrej, Vigu und Vaudejs [Vau i Dejës] nach Schkodra zurück. Von dort trat ich nach kurzem Aufenthalt die Rückreise in die Heimat an. [Ausschnitt aus: Maximilian Lambertz: Bericht über meine linguistische Studien in Albanien vom Mitte Mai bis Ende August 1916. in: Anzeiger der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien, Phil.-hist. Kl., Wien, 53 (1916) Nr. XX, S. 122-146.] Raporti i Udhëtimit në Shqipërinë e Veriut në Vitin 1916 Pjesa dërrmuese e fotografive shqiptare të koleksionit të Maks Lambercit u realizua gjatë udhëtimit të tij në verë të vitit 1916, kryesisht në Mirditë. Janë fotografi të peizazheve të Mirditës dhe të Shqipërisë se Veriut, të mirditorëve, dhe të fshatrave dhe ndërtesave të tyre në mes të Luftës së Parë Botërore. Ka edhe një fotografi të bukur të Tiranës. Fotografitë e Koleksionit të Maks Lambercit, të botuara për herë të parë në albumin fotografik: “Dritëshkronja: fotografia e hershme nga Shqipëria dhe Ballkani jugperëndimor”, Prishtinë 2007, ndodhën tani në Bildarchiv të Bibliotekës Kombëtare të Austrisë në Vjenë (www.bildarchiv.at), të cilit jemi mirënjohës për lejen për t’i paraqitur këtu. Fatmirësisht, për identifikimin e fotografive të koleksionit, ekziston një raport me shkrim të Lambercit për udhëtimin e tij në Mirditë në atë vit. Ky shkrim, me titullin “Raport mbi studimet e mia gjuhësore në Shqipëri nga mesi i majit deri në fund të gushtit 1916" u botua gjermanisht në gazetën e Akademisë Perandorake të Shkencave në Vjenë, po në vitin 1916. Një pjesë të këtij raporti po e japim këtu të përkthyer në gjuhën shqipe. Është fjala për pjesën që lidhet drejtpërsëdrejti me udhëtimin e Lambercit në Mirditë, duke përjashtuar këtu materialin gjuhësor. Në pranverë të vitit 1916, Komisioni për Ballkanin i Akademisë Perandorake të Shkencave në Vjenë më dha detyrën që të merrja pjesë në një ekspeditë ballkanike të organizuar nga Akademia Perandorake e Shkencave në bashkëpunim me Ministrinë Perandorake të Arsimit dhe të Pedagogjisë dhe me Zyrën e Thesarit Perandorak me qëllim kryerjen e hulumtimeve gjuhësore dhe folklorike në Shqipëri. U nisa nga Vjena më 19 maj [1916] bashkë me historianin e artit dhe epigrafistin e ekspeditës. Pas një qëndrimi të shkurtër në Sarajevë, i cili u shfrytëzua për kërkime në muzeumin krahinor, u nisëm për në Kotorr dhe pastaj u ngjitëm në Lovçen, për në Cetinje dhe Podgoricë. Këtu u ndava nga bashkudhëtarët e mi dhe u nisa për në fisin Gruda. Ky fis shqiptar, i cili gjeografikisht është më i largëti, banon në malet në lindje të Podgoricës në luginën e Cemit, në fshatrat Dinoshë, Pikalë, Prift, Lofkë, Bozhaj dhe Selishtë. Baroni Nopça kishte udhëtuar në këtë krahinë në verë të vitit 1907 për të shkuar në Shalë dhe Kelmend. Më 28 maj arrita në Prift, një vendbanim midis Pikalës dhe Lofkës ku banon famullitari i Grudës. Nuk është një fshat i vërtetë, por ka një qelë të re të ndërtuar me fondet e monarkisë sonë, dhe një kishë, e cila ndodhet disa minuta prej saj. Emri i vendbanimit Prifti, si shumë toponime shqiptare, vjen nga emri ose titulli i banorit të parë. Për shembull, toponimi Domgjoni i cili ekziston në disa krahina të Shqipërisë së Veriut, do të thotë vendi ku ka banuar një famullitar me emrin Gjon, rreth të cilit u krijua një fshat. Toponimet e shumta që mbarojnë me -aj janë emra fisesh njësoj si toponimet tona gjermanisht me -ing, -ingen, - ungen. Famullitari i tanishëm i Grudës është françeskani mjaft mirëdashës, Bonaventura Gjeçaj, shqiptar, i cili quhet nga besimtarët e famullisë, Pater Bona, një shembull i mirë i antipatisë që kane shqiptarët për emra të gjatë. Ai dhe Togeri Çuninka [Czuninka], i cili administronte Grudën asokohe, më pritën përzemërsisht. Si pasojë qeshë në gjendje të kryeja hulumtimet e mia në mes të Grudës pa vështirësi sepse banorët e fshatrave përreth mblidheshin në Prift për shërbesa fetare, për të marrë pjesën e bereqetit prej qeverisë, dhe për zgjidhjen e mosmarrëveshjeve ligjore para gjykatësit të caktuar nga komandanti. Bisedoja me ta për të dëgjuar dialektin e tyre dhe, pasi e tejkaluan mosbesimin fillestar ndaj meje dhe u bindën se nuk kisha ardhur në luginën e tyre për të ndërtuar ndonjë fabrikë, ata më kënduan këngë me lahutë, të cilat i shënova me shkrim… Pas disa ditëve atje, isha në gjendje të kuptoja deri diku dialektin e fisit të njerëzishëm Gruda. Do të kisha dashur të qëndroja më gjatë në luginën e bukur të Cemit, por doja të shkoja në Shkodër, qendrën shpirtërore të Shqipërisë së Veriut. Kështu mora rrugën për në Podgoricë dhe, duke qenë se bashkudhëtarët e mi u shpërndanë nëpër Malin e Zi, secili i zënë me fushën e vetë, unë vazhdova rrugën time për në Shkodër vetëm… Kur pjesëmarrësit e tjerë të ekspeditës arritën në Shkodër, udhëtova me ata për në jug. Shkuam në Lezhë, ku bëra një ekskursion në Velë me Doktor Kidriqin [Kidrić]. Nga Lezha, udhëtova me Doktor Bushbekun [Buschbeck] dhe një zotëri gjerman nëpër Fushën e Molungut për në manastirin e vjetër të Rubikut, tani i banuar nga françeskanët, historia e të cilit u hartua nga Millan fon Shuflaj [Milan von Šufflay] në vëllimin e tij tepër informativ Illyrisch-albanische Forschungen [Kërkime iliro-shqiptare], botuar kohët e fundit nga Ludvik fon Talloçi [Ludwig von Thallóczy]. Në Rubik kaluam ditën e Rrëshajës së Madhe. Nga manastiri mikpritës dhe hijerëndë, i vendosur mbi një mal prej të cilit shihej larg, zbritëm në luginën e lumit Fan deri në pikën ku lumi derdhet në Mat dhe, pasi kaluam Matin, arritëm në Milot. Gjatë kësaj pjese të udhëtimit, vura re se dialekti i Mirditës flitet gjithashtu në Malësinë e Lezhës dhe më tej nga Lezha deri në Adriatik. Nga Miloti vazhduam rrugën përmes Mamurrasit për në bazën e vjetër të Skënderbeut, në vendbanimin e bukur të Krujës me burimet e saj natyrore. Dialekti i Krujës nuk përputhet krejtësisht me të folurin e Durrësit dhe të Elbasanit, të përshkruar nga Vajgandi [Weigand], dhe duhet të studiohet dhe të shënohet më vete. Fatkeqësisht kësaj radhe nuk kisha kohë për këtë. Nga Kruja kalëruam përmes fushave pjellore të mbuluara me ullinj për në Tiranë, qyteti i Toptanëve i cili ka një vendndodhje të bukur. Ky qytet, me shtëpitë e tij madhështore dhe mikpritëse myslimane dhe kopshtet e bukura të fshehura në mënyrë idilike prapa mureve të verdha e të larta, që gjithsesi nuk binin në sy, na la mbresa të thella … Në Tiranë u ndava nga bashkudhëtarët e mi, që të mos humbja kohë për detyrën time kryesore, dhe u ktheva në Shkodër nëpërmjet Durrësit dhe Lezhës, ku kësaj radhe vizitova Shëngjinin. Në Shkodër ku qëndrova tri javë, vazhdova studimin e dialektit të Mirditës me Marka Gjokën dhe mirditorë të tjerë. Gjithashtu studiova këngë shqiptare për fëmijë me ndihmën e Patër Vinçenc Prennushit. Disa here shkova edhe në orë mësimi në shkolla të cilat punojnë sipas programeve austriake, edhe shkolla françeskane edhe shkolla publike. Djemtë, shumica e të cilëve ishin të shkathët dhe të talentuar, njohin mirë matematikën, gjeometrinë dhe gramatikën e shqipes. Françeskanët dhe shkolla publike japin edhe mësim të gjermanishtes me mjaft sukses, kështu që shumë të rinj mund të shërbejnë si përkthyes për trupat tona. Në Shkodër shënova trembëdhjetë përralla drejtpërsëdrejti nga goja e tregimtarëve të zhdërvjellët. Nuk pata mundësi të shënoja më shumë sepse nuk kisha kohë të mjaftueshme për të zhvilluar biseda private me vendësit për t’u njohur me ata personalisht, gjë me rëndësi të veçantë në këtë fushë. Ndërkohë, pjesëmarrësit e tjerë në ekspeditë ishin kthyer në Shkodër dhe vendosa të koordinoja planin tim për të shkuar në Mirditë me synimin e tyre për të udhëtuar në Gjakovë nëpërmjet Shqipërinë e Veriut, duke shpresuar kështu të arrija në Mirditë pas ndryshimit të rrugëtimit përmes Shqipërisë së Veriut. U nisëm nga Shkodra në fillim të korrikut dhe kaluam luginën e Kirit përmes Drishtit dhe Prekalit për në krahinën e Shoshit. Mark Lulashi nga Shoshi na shërbeu si udhërrëfyes dhe doli se ishte njohës i mirë i dialektit të Shoshit. Ky dialekt karakterizohet nga shqiptimi i q si c dhe i gj si x. Shënova gjithashtu disa këngë në dialektin e Shoshit. Nga Qafa e Gurakuqit, rruga na çoi përmes Shoshit poshtë në luginën e Lumit të Shalës, prej ku, duke lënë Abatin majtas, u ngjitëm për në Qafën e Agrit, e cila është kufiri midis Shalës dhe Merturit. Prej këndej, u ngjitëm përmbi Palç për në Kotec dhe arritëm në luginën e Drinit para Kotecit. Udhëtimi na kishte ofruar pamje të mrekullueshme që nga Drishti e më tej, me male të larta e hijerëndë, me pamje të paqme të luginës në Shosh dhe peizazhe të errëta të Shalës, por pasi hymë në luginën e Drinit, i cili gjarpëron prej këtu nëpërmjet maleve të Merturit, u mahnitëm nga peizazhet vërtet të mrekullueshme. Nga Koteci në Drin u ngjitëm për në Rajë, vendbanimi i fundit në Mertur. Kjo famulli, ku Patër Gjoni banon në vetmi, ndodhet aty ku Valbona derdhet në Drin. Më lart në luginën e Valbonës banon fisi mysliman Krasniqi, i cili nuk e meriton aspak namin e keq që ka si popull armiqësor dhe i egër. Në Gegëhysen u njoha me disa pleq krasniqas dhe vura re se janë njerëz të mençur që dinë të shijojnë një barcaletë të mirë dhe prapëseprapë janë myslimanë me mjaft dinjitet. Dialekti i tyre i përket grupit të Gjakovës. U ndava nga tre bashkudhëtarët e mi në luginën e Valbonës, të cilët vazhduan në drejtim verilindor, kurse unë u nisa në drejtimin jugor, duke u kthyer në Rajë në hyrjen e luginës. Aty takova Beqir Noun dhe Kolë Markun të cilët u treguan të gatshëm të më informonin për dialektin e tyre në kufirin me Merturin ku, në një qetësi malore të përsosur, Valbona e ëmbël, e mbushur me peshq, derdhet në Drin, dhe fiset Krasniqi, Gashi dhe Thaqi puqen me Merturin… Kalova Valbonën poshtë Rajës dhe pastaj kalova Drinin me një pirogë të dyfishtë jashtëzakonisht primitive. Tash ndodhesha në tokën e Fierzës, në zonën e fisit Thaqi, duke ndjekur për një farë kohe të njëjtën rrugë që kishte bërë Karl Shtajnmeci [Karl Steinmetz] në gusht të vitit 1903, të cilën ai e përshkroi në librin e tij Eine Reise durch die Hochländergaue Oberalbaniens [Një Udhëtim për në Lartësitë e Shqipërisë së Epërme], vëllimi i parë i botuar nga Paç-i [Patsch] në serinë e tij Schriften zur Kunde der Balkanhalbinsel [Shkrime për Njohjen e Gadishullit Ballkanik]. Mirëpo ai udhëtoi në drejtimin e kundërt, nga jugu në veri, kurse unë udhëtova në drejtim të jugut nga Fierza përmes pyllit të virgjër dhe të bukur me lisa të gjatë deri në luginën e bukur të Iballës, e cila rrethohet nga malet nënalpine. Pronari i pirogës i cili më çoi nëpër Drin ishte udhërrëfyes dhe burim i mire informues për dialektin e Thaqit i cili, po ashtu si dialekti i Rajës, është midis Gjakovës dhe Mirditës. Në Iballë, u largova prej rrugës së ndjekur nga Shtajnmeci, i cili kishte ardhur në Iballë nga Kryeziu, dhe u nisa në një shteg në drejtim të perëndimit duke kaluar Qafën e Çomorisë. Prej këndej, shtegu zbret në Lumin e Sapaçit në Berishë dhe pastaj ngjitet me një të përpjetë të fortë në shpatet e Krrabës me pyje të zeza për të kapur Qafën e Tmugut. Prej andej, shtegu zbret përmes lisnajave në luginë pjellore të Qelëzës dhe ngjitet në një nivel prej 820 m. mbi nivelin e detit dhe arrin në rrafshin e Pukës. Gjatë rrugës rreth e rrotull ka pamje të bukura nga ana e veriut. Janë tetë vargmale njëri pas tjetrit, secili me ngjyrën e vetë, nga kodrat e veshura me gjelbërim deri në masivët shkëmborë dhe të hirtë të mbuluar me borë. Prej këndej shihet gjithë Shqipëria e Veriut, deri në Bjeshkët e Shqipërisë së Veriut dhe Malit Shkëlzen. Lart në pllajë kuptohet se romakët kishin pasur sy të mirë, jo vetëm në Carnuntum të Austrisë por edhe këtu në Epicaria [Pukë], duke zgjedhur vendet më të mira për ngulimet e tyre, prej të cilave kontrollonin tërë rajonin. Fon Hani [von Hahn] dhe Baroni Nopça që të dy kishin pranuan se kodra mbi të cilën ndodhet xhamia e tanishme është pa dyshim vendi i fortifikimeve romake. Prova të mjaftueshme janë forma drejtkëndëshe e kodrës, mbetjet e dukshme të mureve antike të ngritura me gurë të gdhendur, disa prej të cilëve janë në muret e armatores, dhe së fundi, minareja e xhamisë e ndërtuar gati tërësisht me gurë romakë. Nga Puka, shkova fillimisht në drejtim të lindjes për në Bicaj në luginën e Fanit të Madh dhe pastaj për një ditë të tërë vazhdova nëpër shtigje të rrezikshme lart mbi luginën e Fanit në drejtim të jugut për në Kalivare. Nga Bicaj isha në Mirditë dhe ndodhesha përsëri në rrugën e përshkuar nga Shtajnmeci. Vendbanimet që kalova në Mirditë, në bajrakun e Spaçit, ishin Shmihija, Shkoza dhe Gojani. Në Kalivare e lashë luginën e Fanit të Madh dhe u ngjita nga lugina e gjelbërt e Lumit të Kalivares përmes Mesulit dhe kullotave malore të Mushtës te Qafa e Lugjut (1465 m.) në shpatin jugor të majës së Munellës. E lashë majën majtas, në të cilën Shtajnmeci u ngjit për herë të parë në vitin 1903 dhe të cilën burrat e Mirditës e përdorën si pikënisje për betejat e tyre me Esadin në vitin e kaluar, dhe u ngjita, i udhëhequr nga Mark Deda i Domgjonit, për orë të tërë përmes ahishteve të bukura ku gjatë rrugës pashë llogore dhe pengesa nga luftimet e fundit. Arritëm në kullotat malore të Domgjonit që ashtu si ato të Mushtës, më dhanë një ndjesi të qartë të bjeshkëve tipike shqiptare, dhe pastaj zbrita në luginën e Fanit të Vogël në drejtim të Domgjonit. Aty u ndava nga Mark Deda të cilin e kisha shfrytëzuar shumë për hulumtimet e mia gjuhësore. Duke zbritur luginën e Fanit të Vogël, mora shtegun pas famullisë së Fanit dhe kalova natën në një vend të fshehtë në shkëmbinjtë i cili përdoret si vendtakimi i krerëve të bajrakut. Të nesërmen arrita në Orosh, kryeqendrën e Mirditës. Vendbanimi i abatit të Mirditës i cili ka një pozicion të mirë, është përshkruar tashmë nga disa udhëtarë, veçanërisht nga A. Degrand në Souvenirs de la Haute-Albanie [Kujtime nga Shqipëria e Epërme] (1903) dhe K. Shtajnmec në librin e lartëpërmendur. Me vendndodhje mbi një brezare në bregun e majtë të Fanit, në mes të rrugës kur ngjitesh prej luginës, Oroshi, me kishën e shkëlqyer që shihet nga larg nga ana jugore, dhe me abacinë e madhe, të kujton Maria-Taferl në vendin tonë. Përballë në një rrëpirë, në formë gjuhe, të Malit të Shejtit ndodhet fshati Orosh. Abati banon tani në Shkodër dhe abacia është bërë selia e komandës ushtarake. Aty bujta disa ditë si mysafir. Qëndrimin tim e shfrytëzova për t’u ngjitur disa herë në fshatin Orosh për të vizituar mirditorët në kullat e tyre dhe për të mësuar më shumë për dialektin e tyre përmes hartimit të fjalëve dhe të bisedave. Vura re me kënaqësi se miqtë e mi mirditorë në Shkodër më kishin mësuar gjuhën e pastër të Mirditës. Me gëzim shfrytëzova rastin për të shkuar në rajonin fqinj të Lurës kur një patrullë e xhandarmërisë u nis nga Oroshi dhe komandanti i saj më ftoi t’a shoqëroja. Kjo është krahina e një prej fiseve më famëkëqij shqiptarë i njohur për egërsinë dhe armiqësinë ndaj të huajve. Unë kisha mësuar për të nga përshkrimet e K. Shtajnmecit në librin e tij Von der Adria zum schwarzen Drin [Nga Adriatiku në Drinin e Zi]. Pas një dite marshimi nga Oroshi arritëm në Lurë. Shtegu shkon majtas nga Mali i Shejtit përmes hapësirës së gjerë të pyllëzuar të Fushës së Shejtit. Në mesditë pushuam nga ana lindore e saj. Aty pamë disa kasolle prej balte dhe shumë kuti konservash ushqimore të zbrazëta me shkronja cirilike, të mbetura prej fushimit serb nga ditët e arratisjes nëpërmjet Shqipërisë të ushtrisë së mundur serbe. Prej këndej shtegu zbret në luginën e Mallës dhe ngjitet prapë majtas përmes një gryke të pyllëzuar për në Lurë të Epërme, e cila ka një vendndodhje të mrekullueshme në një luginë në një lartësi prej 1100 m. Ky vend më kujtoi fshatrat tona të larta të Tirolit: Gurgl dhe Vent. Në atë kohë Batalioni 19 Perandorak i Pushkatarëve ndodhej rastësisht në Lurën e Epërme ku kishte ndërmarrë një ekspeditë. Komandanti i tij, Nënkoloneli Broser, më priti përzemërsisht dhe, duke qenë se i duhej të shkonte nga Lura për në Kthellë dhe Selitë si gjykatës, më pyeti nëse do të kisha dëshirë ta shoqëroja dhe të vija njohuritë e mia të gjuhës vendore në dispozicion të ekspeditës. Unë e pranova propozimin e tij me kënaqësi jo vetëm sepse doja ta ndihmoja, por edhe sepse udhëtimi më dha një mundësi të mirëpritur për t’u njohur me fisin dhe me gjuhën e Kthellës. Pas mbarimit të gjyqit në Kthellë, udhëtova me Batalionin 19 të Pushkatarëve përmes Oroshit dhe Kthellës së Epërme për në Selitë ku në Qafën e Kishës ngritëm fushimin midis kishës dhe famullisë në mes të këtij fisi jopaqësor. Çfarë përjetova gjatë dhjetë ditëve të qëndrimit me Batalionin 19 të Pushkatarëve, ku bashkëpunova ngushtë me oficerët e trupave të cilët ishin mjaft të afrueshëm, në një nga krahinat më të ashpra të Shqipërisë, i përket më shumë një kapitulli të historisë politike të Shqipërisë në këtë kohë të trazuar se sa një raporti shkencor për një institucion akademik. Mjafton të theksohet se si myslimanët e Lurës po ashtu edhe katolikët e Kthellës, që në asnjë mënyrë nuk ishin më të mirë, duhej të mësonin se “kohët e vjetra të arta” në Shqipëri kishin perënduar dhe se qytetërimi evropian, i përfaqësuar nga ushtria austro-hungareze, tash po trokiste në derën e Shqipërisë, e cila deri tani kishte mbetur e mbyllur ndaj çdo përparimi kulturor dhe etik. Pasi kreva detyrën time si “përkthyes gjyqi” dhe pasi mësova diçka për dialektin e këtyre fiseve, i cili është mjaft i ngjashëm me dialektin e Mirditës, u ndava prej zotërinjve të batalionit dhe u ktheva në Shkodër përmes Oroshit, Blinishtit, Ungrejt, Vigut dhe Vaut të Dejës. Dhe pas një qëndrimi të shkurtër, u nisa për në shtëpi. [Nxjerrë nga Maksimilian Lamberc: Raport mbi studimet e mia gjuhësore në Shqipëri nga mesi i majit deri në fund të gushtit 1916 [Bericht über meine linguistische Studien in Albanien vom Mitte Mai bis Ende August 1916]. në: Anzeiger der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien, Phil.-hist. Kl. Vjenë, 53 (1916), Nr. XX, f. 122-146. Përkthyer nga gjermanishtja nga Robert Elsie.]

| Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact |